Étiquette : Beethoven

Maestro Editions Lien/Link: https://www.maestroeditions.com/

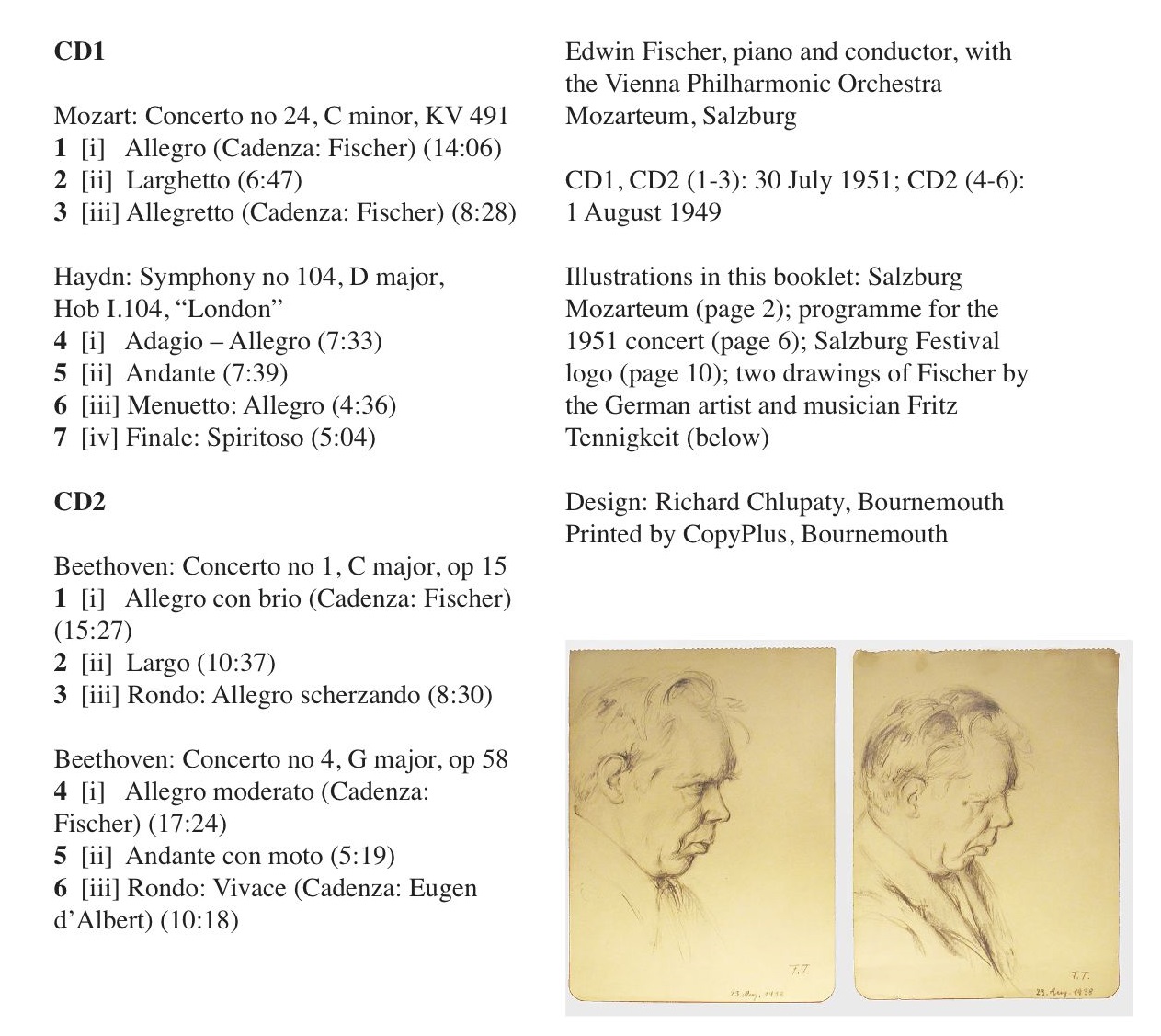

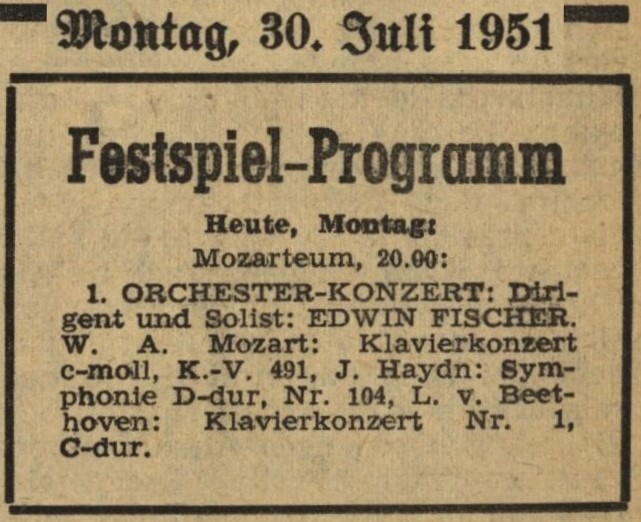

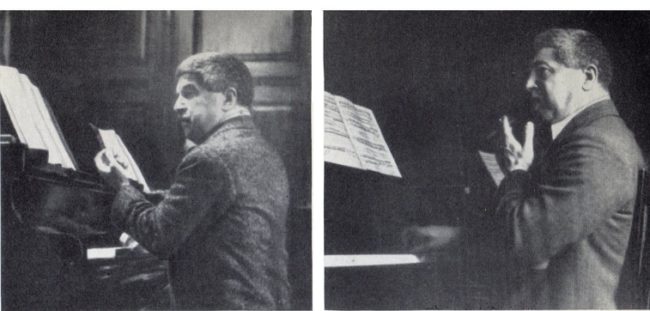

Maestro Editions qui a déjà publié le concert dirigé par Edwin Fischer lors du Festival de Strasbourg 1953, nous offre des inédits d’importance provenant cette fois du Festival de Salzbourg, où Fischer dirige les Wiener Philharmoniker. Il s’agit de la totalité du concert du 30 juillet 1951 (Mozart Concerto n°24 K.491, Haydn Symphonie n°104 et Beethoven Concerto n°1 Op.15) et du seul enregistrement qui subsiste du concert du 1er août 1949 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58).

Ces enregistrements proviennent des archives de Paul Badura-Skoda (1927-2019), qui les a transmis à Roger Smithson en vue d’une possible publication. Le concert de 1951, enregistré sur bande magnétique avec une très bonne qualité sonore, présentait cependant certains problèmes, notamment il manquait les dernières notes du Concerto de Beethoven et il y avait des distorsions gênantes dans la Symphonie de Haydn. Fort heureusement, il existait une autre source, certes inférieure pour le Beethoven, mais qui était complète, et Andrew Hallifax a su rendre acceptable les saturations dans le Haydn.

Le Concerto n°24 K.491 était le préféré de Fischer, si l’on en juge par le fait qu’il l’a joué quatre fois au Festival de Salzbourg (1947, 1949, 1951 et 1954). Il en existe deux autres enregistrements (London Philharmonic / Collingwood 1937, Royal Danish Orchestra 1954), et si les trois interprétations sont différentes, celle-ci est la plus vivante et on notera également la qualité du dialogue avec les instruments à vent de l’orchestre.

Concernant la Symphonie de Haydn, quoi de mieux que de laisser la parole à Paul Badura-Skoda?: ‘Du vivant de Fischer, j’ai constitué à sa demande des archives sonores avec des enregistrements sur bande de toutes sortes. Un jour, j’ai fait écouter à un chef d’orchestre renommé, sans citer le nom de Fischer, une bande contenant une retransmission radio du concert du Festival de Salzbourg au cours duquel le maître Edwin avait dirigé la Symphonie en ré majeur n°104 de Haydn. Celui-ci l’écouta d’abord à contrecœur, puis avec grand intérêt. ‘C’est magnifique, je ne l’ai jamais entendue aussi magistralement’, s’exclama-t-il. ‘Qui dirige ? Toscanini ?’. Il a été plus qu’étonné lorsque je lui ai dit qu’il s’agissait ‘seulement’ du ‘pianiste-chef d’orchestre’ Edwin Fischer. Je n’ai pas pu assister à un seul des concerts que Fischer a donnés avec son propre orchestre de chambre, mais ses concerts avec l’Orchestre Philharmonique de Vienne pendant le Festival de Salzbourg sont restés gravés dans ma mémoire, et l’Orchestre Philharmonique lui-même ne les a pas oubliés’.

L’enregistrement du Concerto n°1 Op.15 de Beethoven est un événement, car la seule version que l’on connaissait jusqu’à présent (BPO 1943) est très déficiente sur le plan sonore, et l’interprétation spontanée (selon Badura-Skoda) de Fischer nous confirme qu’il était dans un grand jour. Le Concerto n°4 Op.58 provient de disques à gravure directe de qualité variable, mais le premier mouvement est quand même satisfaisant.

Notons enfin que le travail de restauration effectué par Andrew Hallifax est très respectueux de l’interprétation de Fischer. Cet ingénieur du son est connu pour les très beaux reports qu’il a effectués pour le site ‘Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music’ ainsi que pour le label APR.

____________

Maestro Editions, which has already published the concert conducted by Edwin Fischer at the 1953 Strasbourg Festival, is now offering us important previously unreleased material from the Salzburg Festival, where Fischer conducts the Wiener Philharmoniker. It is comprised of the entire concert of 30 July 1951 (Mozart Concerto No. 24 K.491, Haydn Symphony No. 104 and Beethoven Concerto No. 1 Op.15) and of the only surviving recording of the concert of 1 August 1949 (Beethoven Concerto No. 4 Op.58).

These recordings come from the archives of Paul Badura-Skoda (1927-2019), who lent them to Roger Smithson for possible publication. The 1951 concert, recorded on magnetic tape with very good sound quality, nevertheless presented certain problems, especially the last notes of the Beethoven Concerto were missing and there were annoying distortions in the Haydn Symphony. Fortunately, there was another source, admittedly inferior for the Beethoven, but which was complete, and Andrew Hallifax was able to make the saturations in the Haydn acceptable.

Concerto No. 24 K.491 was Fischer’s favourite, judging by the fact that he played it four times at the Salzburg Festival (1947, 1949, 1951 and 1954). There are two other recordings (London Philharmonic / Collingwood 1937, Royal Danish Orchestra 1954), and although the three interpretations are different, this is the most lively, and the quality of the dialogue with the orchestra’s wind instruments is also noteworthy.

For the Haydn’s Symphony, what better way than to let Paul Badura-Skoda have his say?:’While Fischer was still alive, I compiled a sound archive with all kinds of tape recordings on his behalf. Once, without mentioning Fischer’s name, I played a tape to a well-known conductor which contained a radio broadcast of the Salzburg Festival concert at which Master Edwin had conducted Haydn’s D major Symphony No. 104. He first listened reluctantly and then with great interest. he exclaimed: ‘That’s marvellous, I’ve never heard it so masterly. Who is conducting? Toscanini?’. He was more than astonished when I told him that it was ‘only’ the ‘conducting piano player’ Edwin Fischer. I was never able to attend any of the concerts that Fischer gave with his own chamber orchestra, but I still have vivid memories of his concerts with the Vienna Philharmonic during the Salzburg Festivals, and the Philharmonic itself has not forgotten them either’.

The recording of Beethoven’s Concerto No. 1 Op.15 is an event, because the only version we knew of until now (BPO 1943) is very deficient in sound, and Fischer’s spontaneous interpretation (according to Badura-Skoda) confirms that he was on a great day. Concerto No. 4 Op.58 comes from transcription discs of variable quality, but the first movement is nonetheless satisfactory.

Finally, it should be noted that the restoration work carried out by Andrew Hallifax is very respectful of Fischer’s interpretation. This sound engineer is renowned for the fine transfers he has produced for the Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music website and for the APR label.

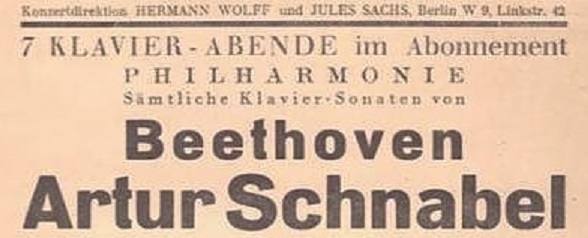

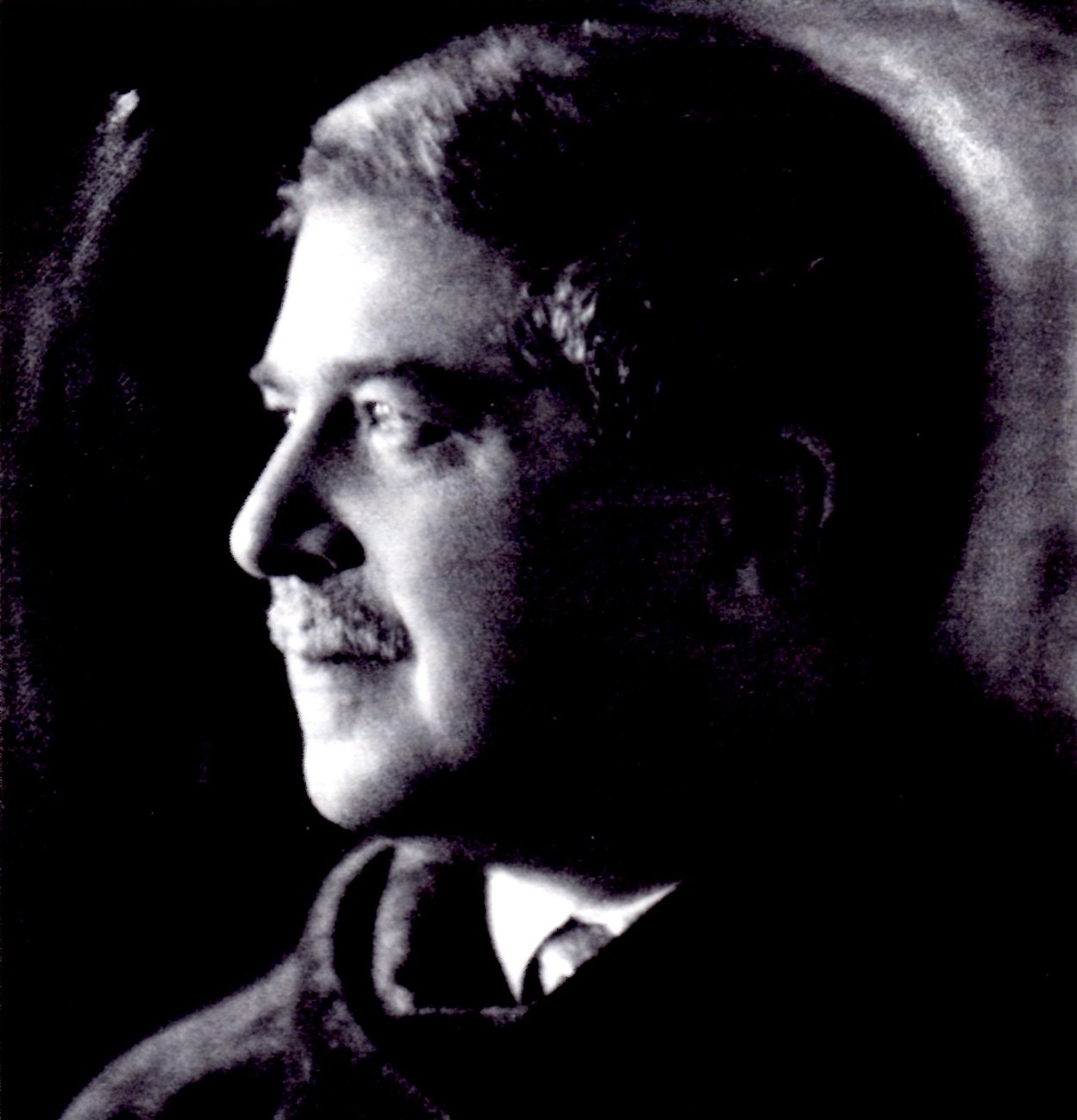

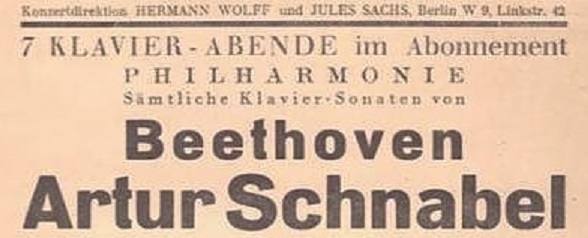

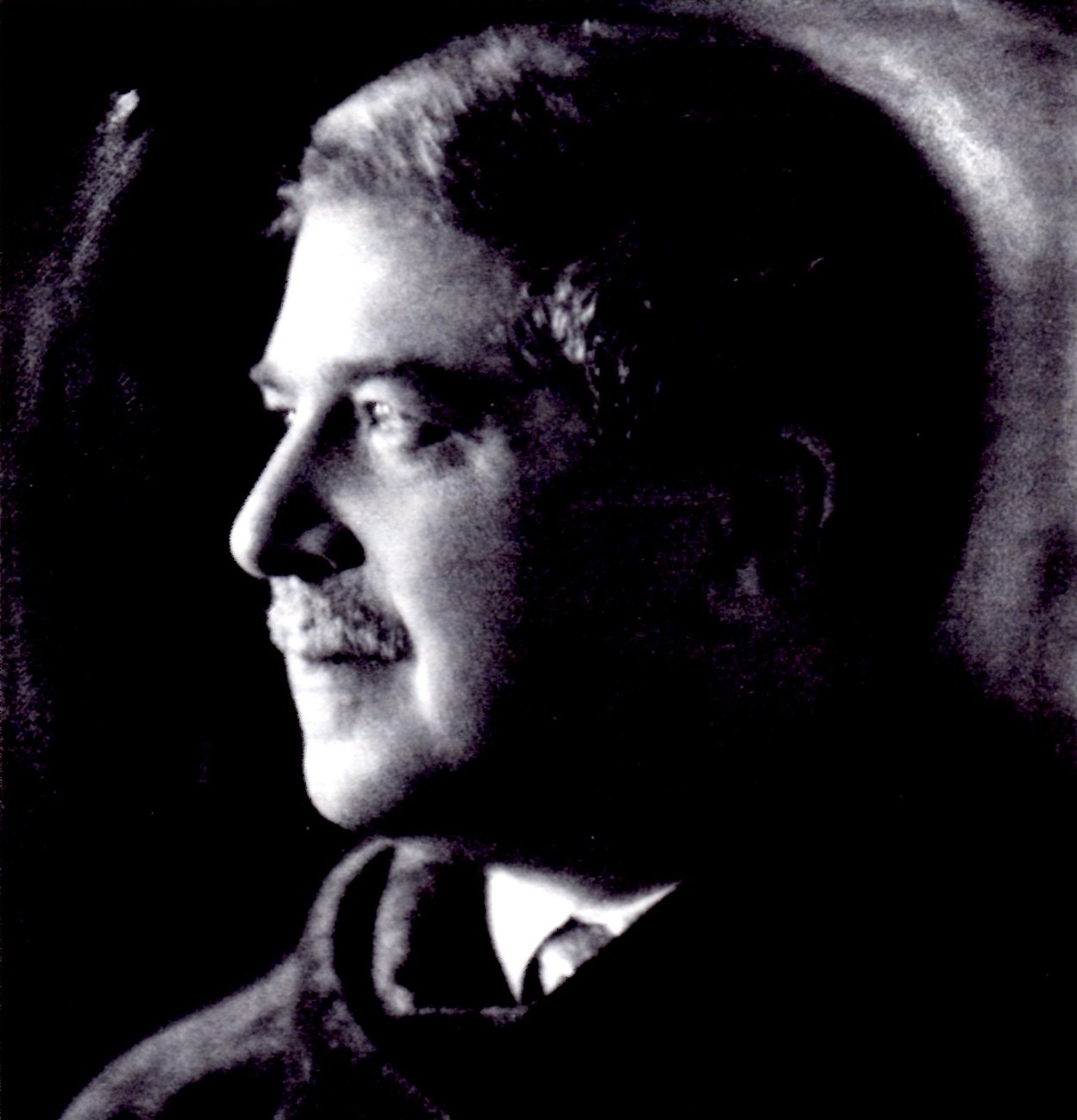

Artur Schnabel a enregistré à Londres au Studio n°3 d’Abbey Road, entre janvier 1932 et novembre 1935 (avec quelques corrections en janvier 1937), la toute première intégrale des Sonates pour piano de Beethoven.

Il a également joué quatre fois cette intégrale sous forme d’un cycle de sept récitals, toujours composés de la même façon, et dont chacun regroupait soit quatre, soit cinq, sonates de diverses périodes.

Programme I : Sonates n°15 Op.28 – n°31 Op.110 // n°1 Op.2 n°1 – n°16 Op.31 n°1

Programme II: Sonates n°18 Op.31 n°3 – n°28 Op.101 // n°22 Op.54 – n°8 Op.13 – n°3 Op.2 n°3

Programme III: Sonates n°2 Op.2 n°2 – n°23 Op.57 // n°19 Op.49 n°1 – n°27 Op.90 – n°11 Op.22

Programme IV: Sonates n°12 Op.26 – n°17 Op.31 n°2 // n°5 Op.10 n°1 – n°6 Op.10 n°2 – n°26 Op.81a

Programme V: Sonates n°4 Op.7 – n°14 Op.27 n°2 // n°10 Op.14 n°2 – n°29 Op.106

Programme VI: Sonates n°13 Op.27 n°1 – n°21 Op.53 // n°20 Op.49 n°2 – n°30 Op.109

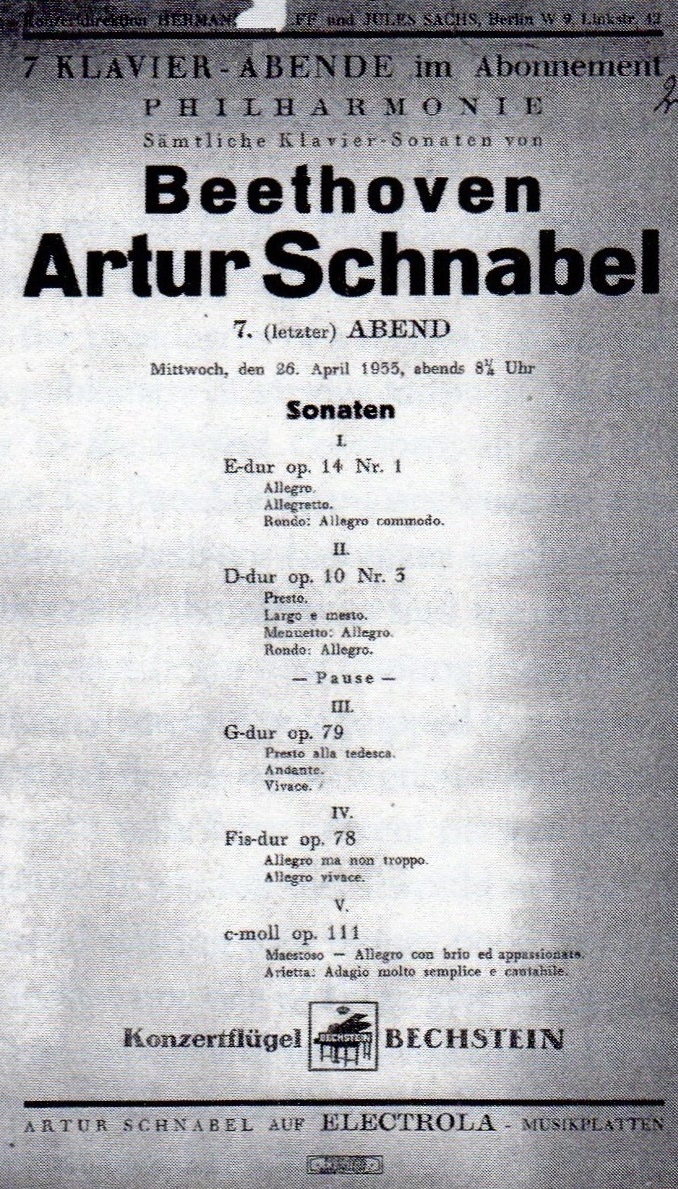

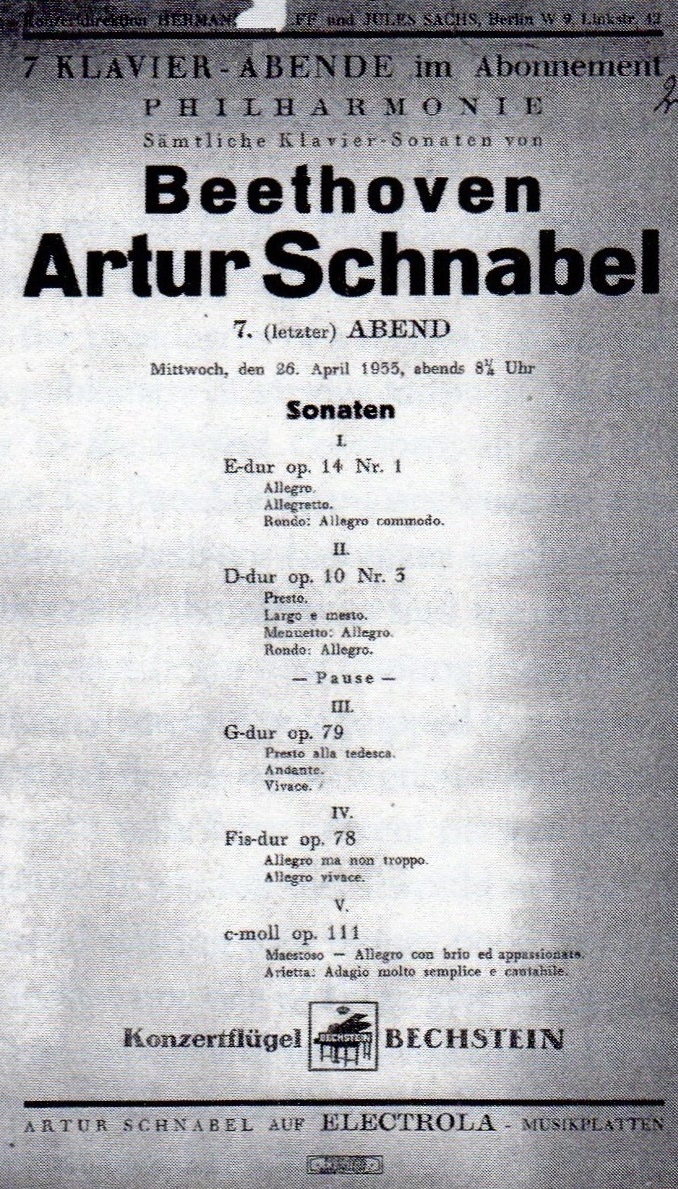

Programme VII:Sonates n° 9 Op.14 n°1 – n°7 Op.10 n¨3 // n°25 Op.79 – n°24 Op.78 – n°32 Op.111

Entre 1924 et 1927, Schnabel a publié chez Ullstein son édition intégrale des 32 Sonates.

La première intégrale a été donnée en 1927 à la Volksbühne de Berlin à l’occasion du Centenaire de la mort de Beethoven. Les récitals ont été donnés le dimanche à 11h30 aux dates suivantes: 9, 16 & 23 Janvier; 6, 13, 20 & 27 février. Le détail des programmes est donné ICI

La deuxième intégrale a été donnée au Queen’s Hall de Londres en octobre-novembre 1932.

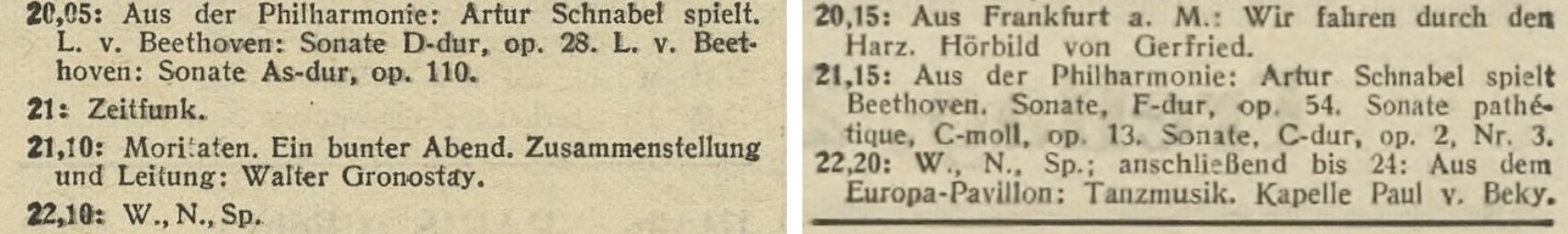

La troisième intégrale, de nouveau à Berlin, mais à la Philharmonie, en janvier-avril 1933, a pu être menée à bien malgré la prise de pouvoir d’Hitler.

Les dates des récitals sont les suivantes: 5 & 20 Janvier; 21 Février; 3 & 16 Mars; 6 & 26 Avril 1933 (dernier concert de Schnabel en Allemagne). Le détail des programmes est donné ICI

Sa réplique aux autorités allemandes lui notifiant à la fin de ce concert qu’il ne pourra pas participer aux concerts berlinois célébrant le centenaire Brahms est restée celèbre: « Mon sang n’est peut-être pas pur, mais j’ai du sang-froid. Adieu! » Il a du quitter définitivement Berlin où il s’était établi en 1900.

Au cours de ce cycle, Schnabel se rend par deux fois à Londres en février, puis en avril, pour des enregistrements beethovéniens (3 et 17 février: Sonate n°15; 16 février Concerto n°4; 17 février Concerto n°3; et du 9 au 19 avril: Sonates n°2, 6, 11, 14, 20, 22, 23 & 26).

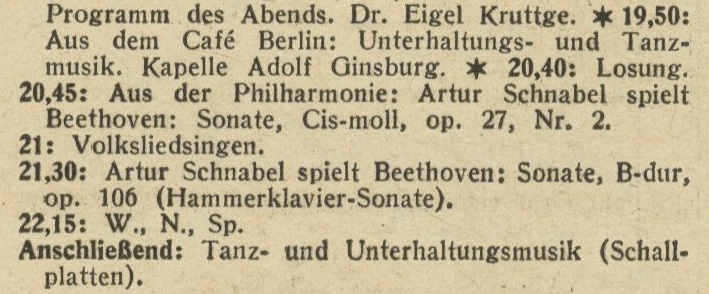

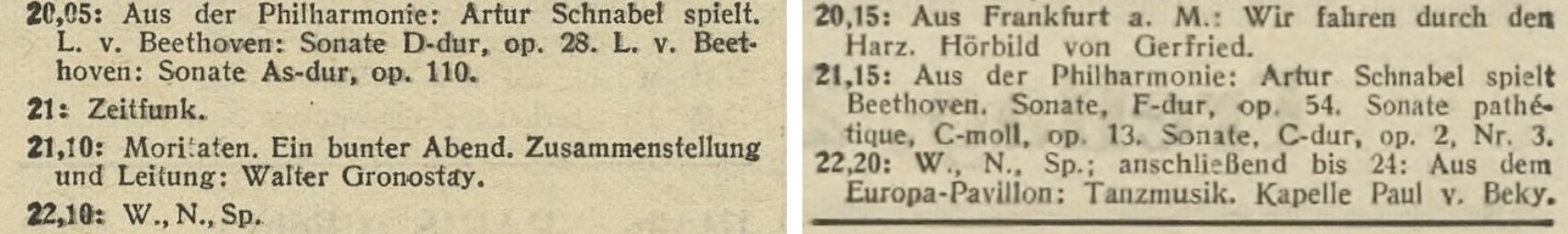

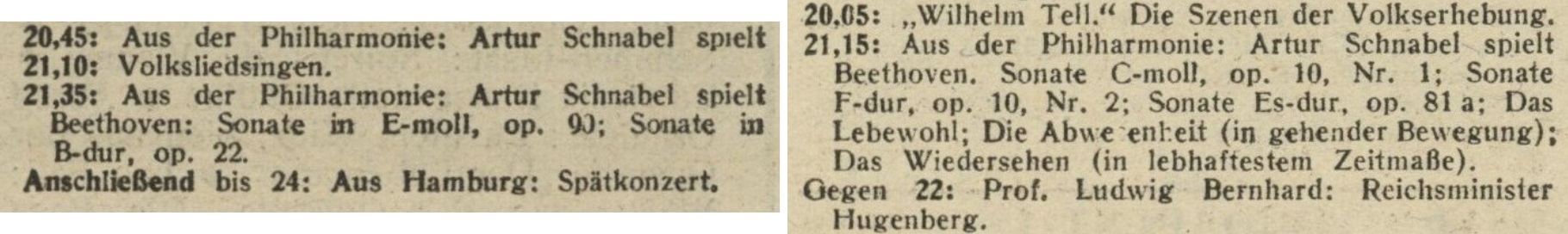

Pour la première fois, Schnabel a autorisé des retransmissions radiophoniques d’au moins une partie de chaque récital. Elles ont été brutalement interdites après le quatrième programme (3 mars). La dernière sonate retransmise sera ainsi la n°26 Op.81a « Das Lebewohl »…

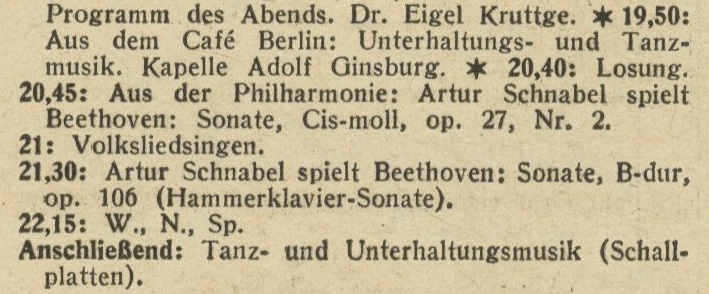

Les extraits retransmis par Radio-Berlin sont listés ci-dessous:

Radio Berlin:Programme I (Part I) 5.01 – Programme II (Part II) 20.01

Radio Berlin:Programme III 21.02 – Programme IV (Part II) 3.03

Radio Berlin: Programme V 16.03 (retransmission annulée/broadcast cancelled)

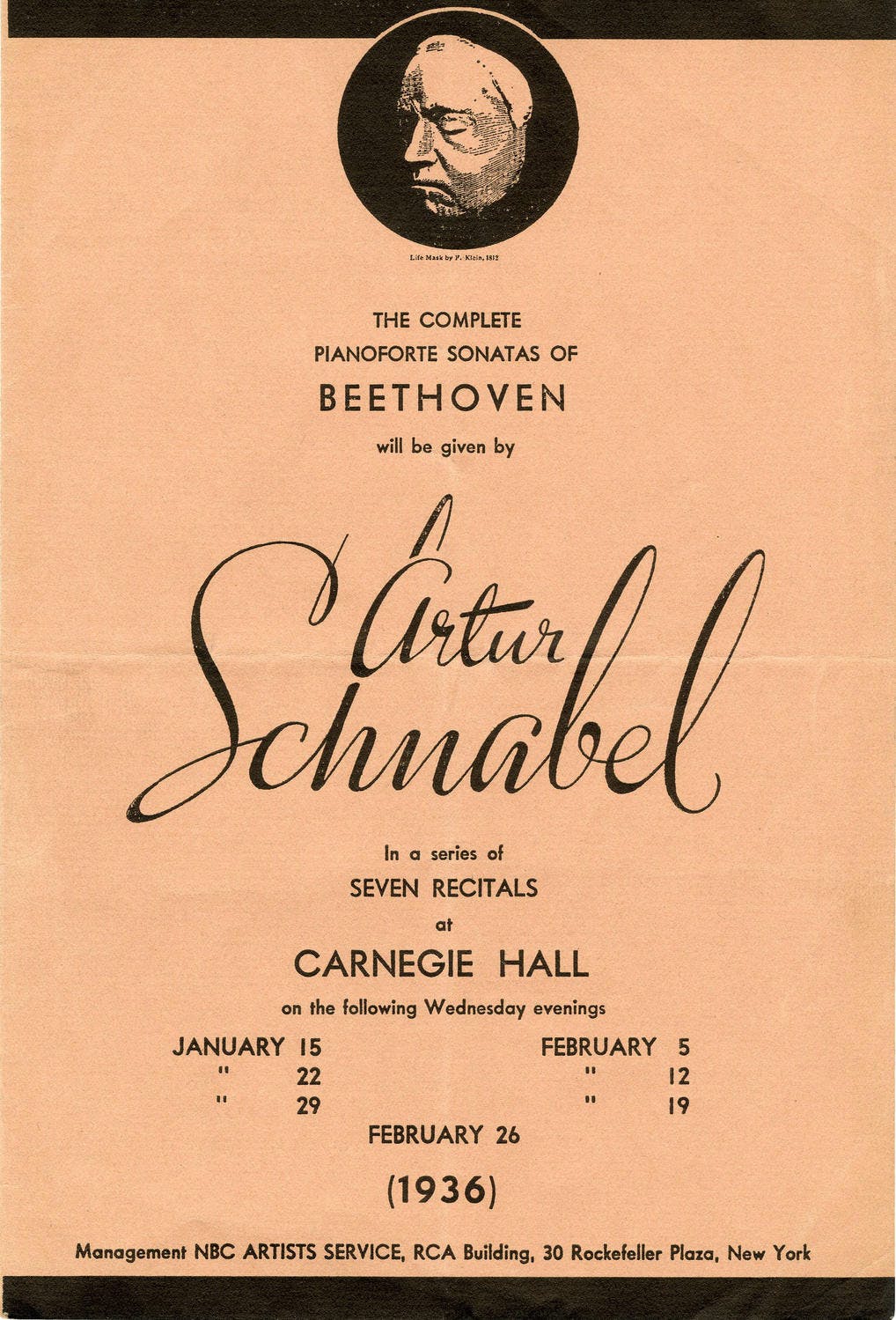

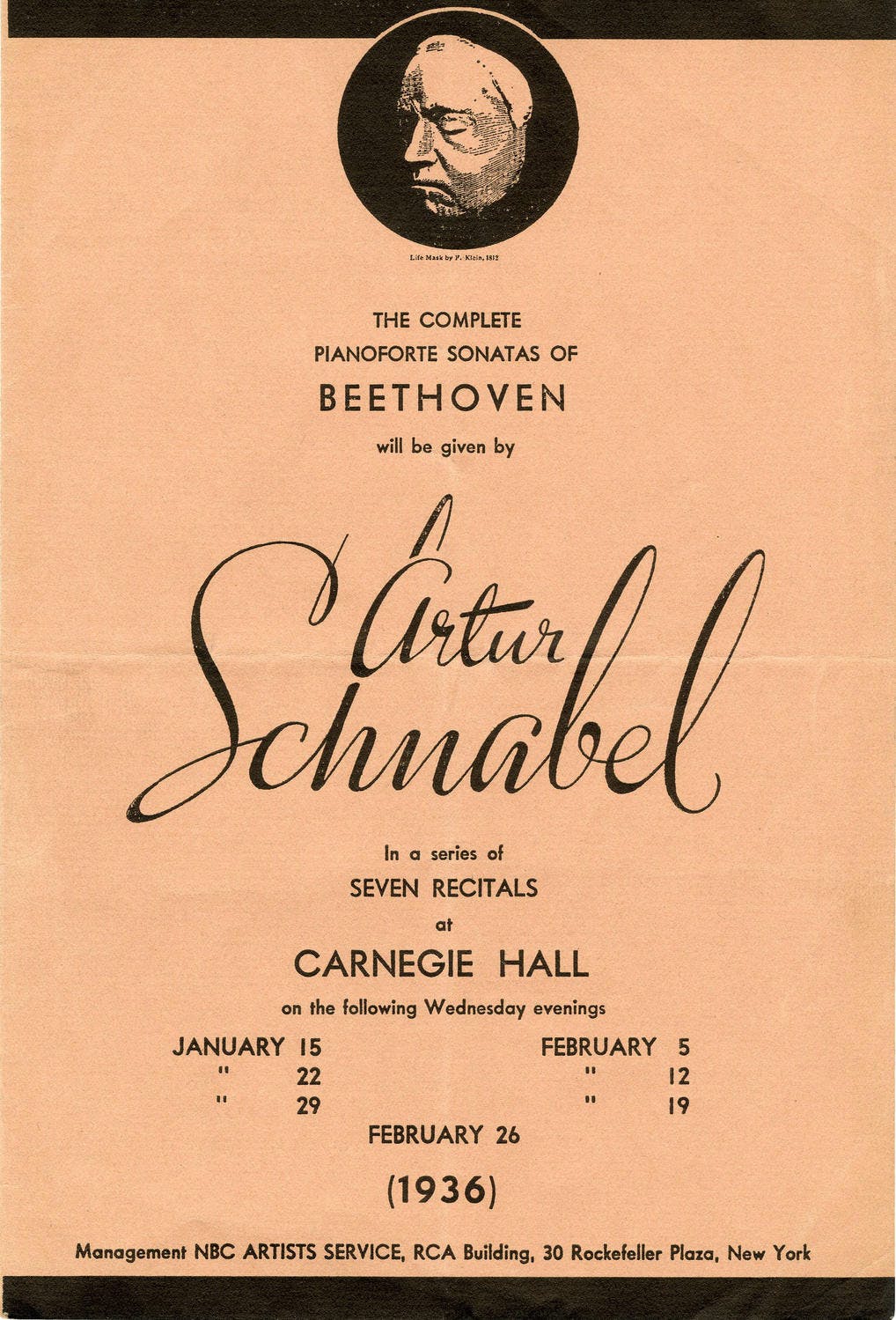

La dernière intégrale a été donnée en janvier-février 1936 au Carnegie Hall de New York sur un piano Steinway (au lieu du Bechstein joué lors des cycles précédents). Arrivé à New-York le 9 janvier à bord du paquebot Île-de France, Schnabel a donné ses 7 récitals les 15, 22 & 29 janvier, et les 5, 12, 19 & 26 février 1936.

Artur Schnabel made in London at Abbey Road Studio n°3, between January 1932 and November 1935 (with some corrections in January 1937), the very first complete recording of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas.

He also gave four complete performances of the 32 Sonatas as a cycle of seven recitals, always organized in the same way, each one being comprised of either four or five Sonatas from different periods.

Program I : Sonatas n°15 Op.28 – n°31 Op.110 // n°1 Op.2 n°1 – n°16 Op.31 n°1

Program II: Sonatas n°18 Op.31 n°3 – n°28 Op.101 // n°22 Op.54 – n°8 Op.13 – n°3 Op.2 n°3

Program III: Sonatas n°2 Op.2 n°2 – n°23 Op.57 // n°19 Op.49 n°1 – n°27 Op.90 – n°11 Op.22

Program IV: Sonatas n°12 Op.26 – n°17 Op.31 n°2 // n°5 Op.10 n°1 – n°6 Op.10 n°2 – n°26 Op.81a

Program V: Sonatas n°4 Op.7 – n°14 Op.27 n°2 // n°10 Op.14 n°2 – n°29 Op.106

Program VI: Sonatas n°13 Op.27 n°1 – n°21 Op.53 // n°20 Op.49 n°2 – n°30 Op.109

Program VII:Sonatas n° 9 Op.14 n°1 – n°7 Op.10 n¨3 // n°25 Op.79 – n°24 Op.78 – n°32 Op.111

Between 1924 and 1927, Schnabel published (Ullstein) his printed edition of the complete 32 Sonatas.

The first complete performance was given in 1927 at the Berlin Volksbühne for the Centenary of Beethoven’s death. The recitals were on Sundays at 11:30 on the following dates: 9, 16 & 23 January; 6, 13, 20 & 27 February. The detailed programs are HERE

The second complete performance was given at London’s Queen’s Hall in October-November 1932.

The third one, again in Berlin, but at the Philharmonie, in January-April 1933, was given complete in spite of Hitler’s taking of power.

The dates of the were as follows: 5 & 20 January; 21 February; 3 & 16 March; 6 & 26 April 1933, which was Schnabel’s very last concert in Germany. The detailed programs are HERE

His answer to the German authorities notifying him at the end of this concert that he was barred from taking part in the Berlin concerts celebrating Brahms’ centenary has remained famous: « I may not be pure-blooded, but I am cold-blooded. Good-bye! » He was obliged to leave for ever Berlin where he lived since 1900.

During this cycle, Schnabel travelled twice to London in February and in April for Beethoven recordings (3 et 17 February: Sonata n°15; 16 February: Concerto n°4; 17 February:Concerto n°3; and from 9 to 19 April: Sonatas n°2, 6, 11, 14, 20, 22, 23 & 26).

For the first time, Schnabel allowed broadcasts of at least a part of each recital. They were brutally forbidden after the fourth program (3 March). The last Sonata to be broadcast was thus n°26 Op.81a « Das Lebewohl »…

The excerpts broadcast by Radio-Berlin are listed below:

Radio Berlin:Programme I (Part I) 5 January – Programme II (Part II) 20 January

Radio Berlin:Programme III 21 February – Programme IV (Part II) 3 March

Radio Berlin: Programme V 16 March (broadcast cancelled)

The last complete performance was given in January-February 1936 at Carnegie Hall in New York on a Steinway piano (instead of the Bechstein for the earlier cycles). Schnabel arrived in New-York on 9 January on bord the liner Île-de France. He gave his 7 recitals on Wednesdays 15, 22 & 29 January, et 5, 12, 19 & 26 February 1936.

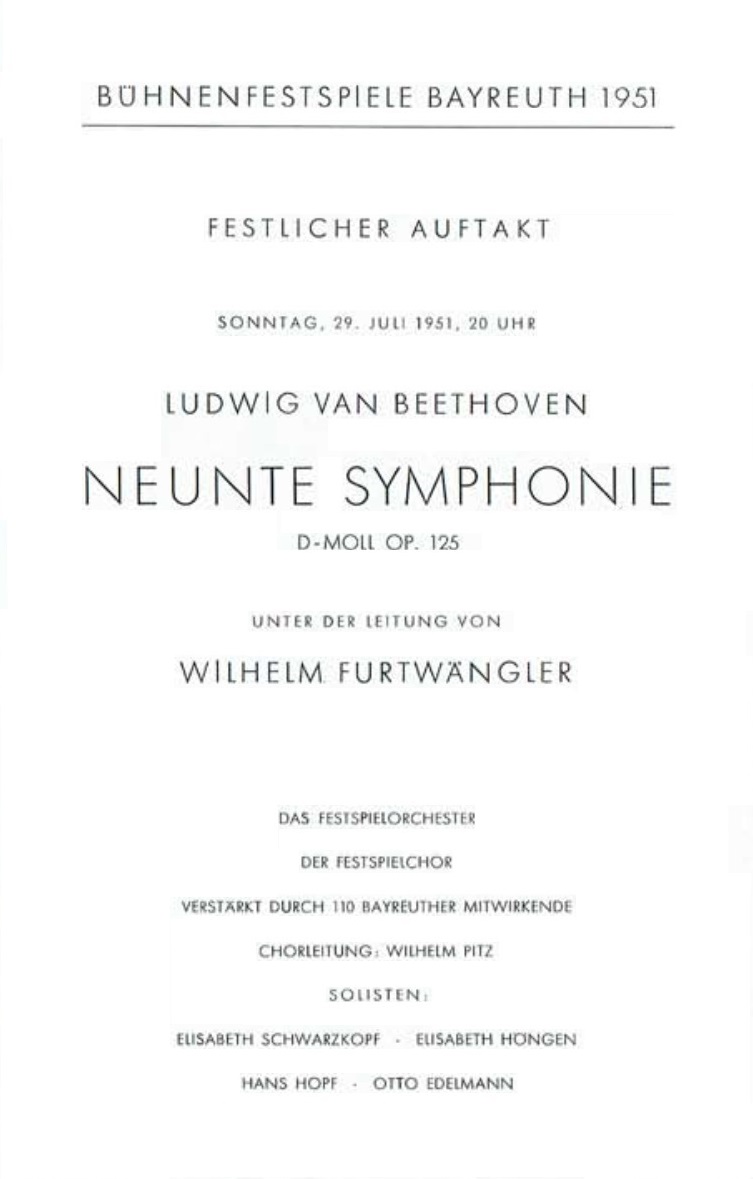

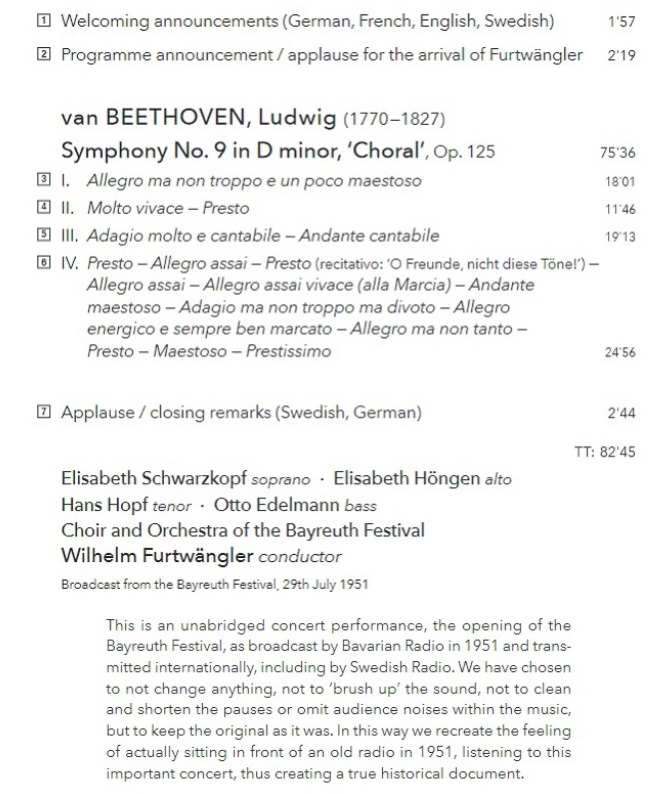

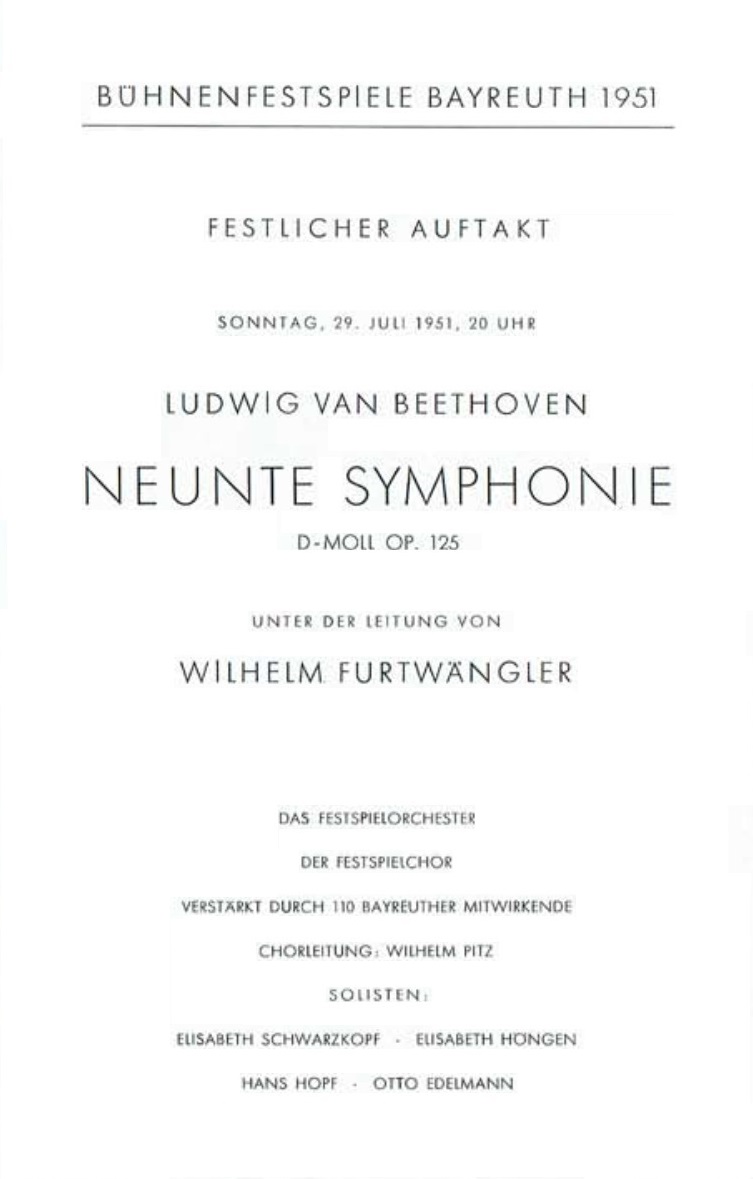

Beethoven Symphonie n°9 Op125 Das Festspielorchester – Das Festspielchor Bayreuth

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth Höngen,Hans Hopf, Otto Edelmann

Dir: Wilhelm Furtwängler

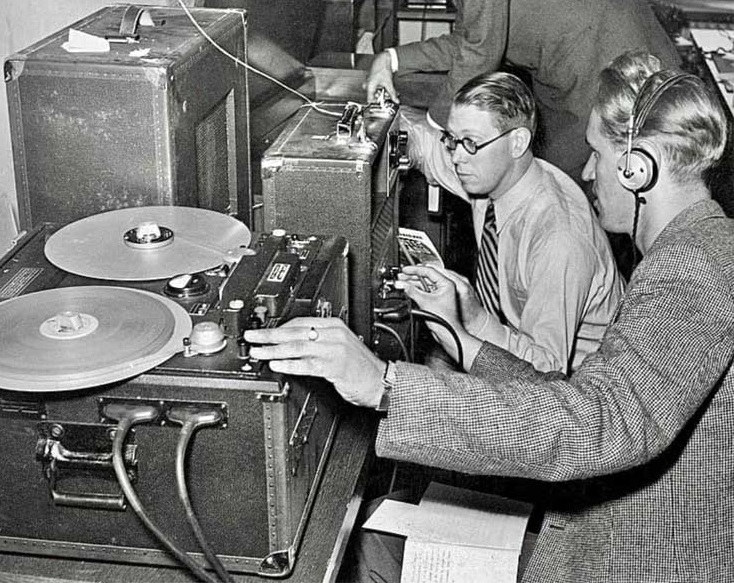

La firme suédoise BIS vient d’éditer en SACD hybride (BIS-9060) et également sous forme de téléchargement HD (24 bits/96 KHz) la captation par la Radio Suédoise de la retransmission en direct de ce concert par la Radiodiffusion Bavaroise (Bayerischer Rundfunk), qui de manière inattendue a été conservée dans ses Archives.

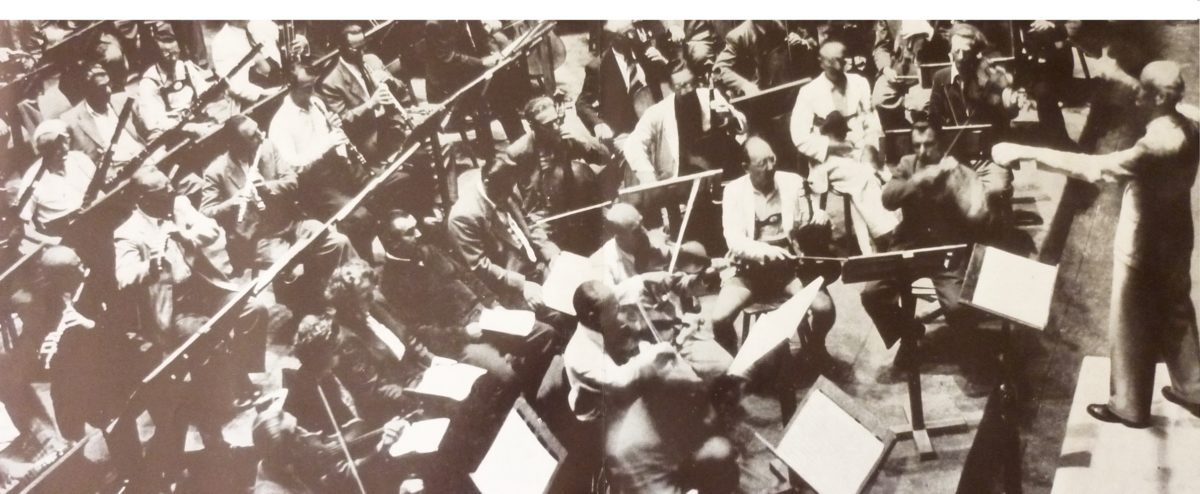

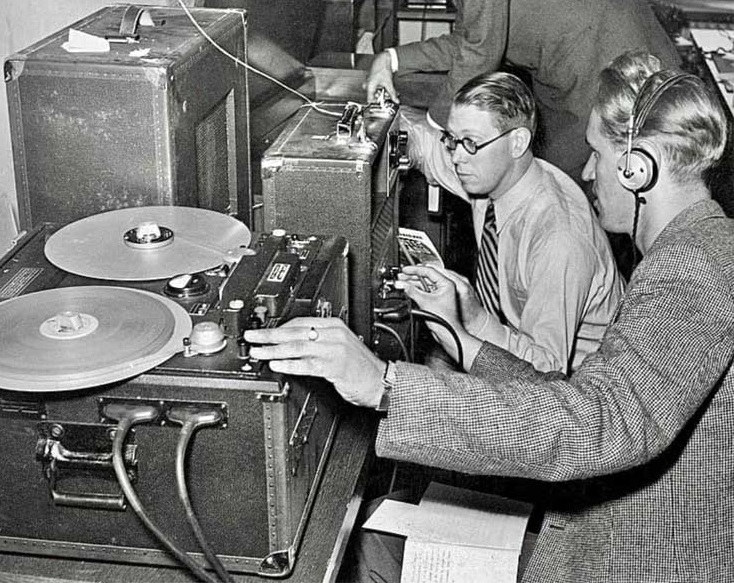

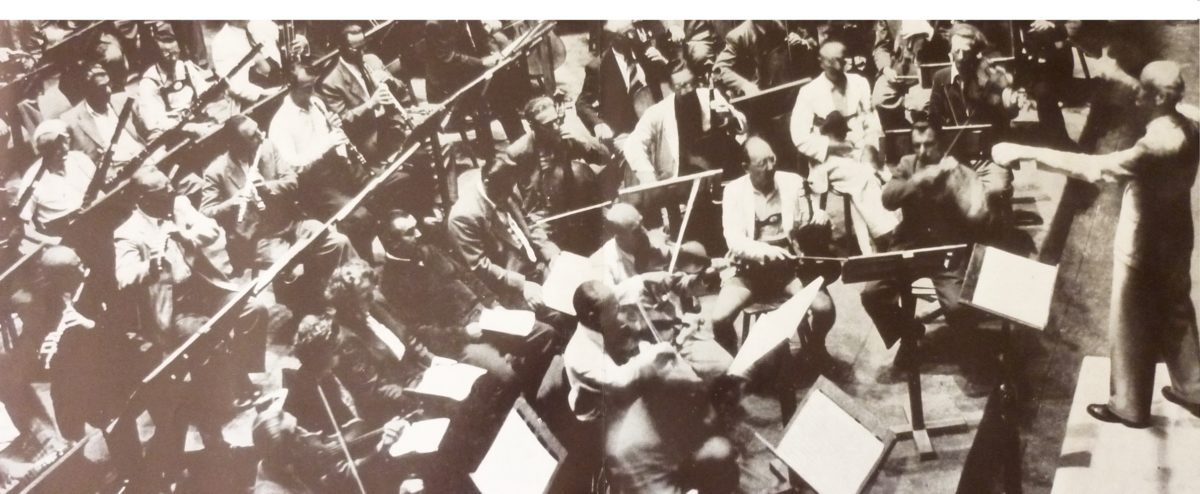

On sait que l’édition discographique par EMI résulte d’un montage provenant, selon Henning Smidth, en grande partie des répétitions et pour partie seulement du concert du 29 juillet. Il devrait s’agir des répétitions du matin et de l’après-midi du concert, car le 27, jour d’arrivée de Furtwängler à Bayreuth et le 28, les premières répétitions ont eu lieu dans une autre salle (voir la photo ci-dessus) à l’acoustique différente et, selon Klaus Lang, avec une disposition de l’orchestre un peu différente de celle du concert pour lequel une disposition classique a été adoptée.

Pour ce premier Festival d’après-guerre, l’orchestre comprenait, en son plein effectif qui n’est certes pas déployé ici, 150 musiciens provenant de 40 orchestres différents de l’Allemagne de l’Ouest (BRD), y compris Berlin, et de l’Allemagne de l’Est (DDR). Pour la Neuvième Symphonie, le chœur comprenait 150 choristes, issus des Opéras allemands, et il était renforcé par 110 choristes originaires de Bayreuth. L’ensemble des musiciens était disposé sur le plateau et sur la fosse d’orchestre, recouverte pour l’occasion. On imagine quel tour de force cela représentait du point de vue de la direction d’orchestre que de monter en si peu de temps une telle exécution avec autant de musiciens provenant de lieux aussi divers jouant pour la première fois ensemble.

I- Les échanges entre Wilhelm Furtwängler et Wieland Wagner:

Wieland Wagner a pu seulement obtenir de Furtwängler qu’il dirige à Bayreuth cette Neuvième Symphonie. Il a de plus refusé d’en diriger une deuxième exécution le 20 août.

Concernant les solistes, Wieland Wagner n’a pas réussi à le convaincre (lettres des 5 février et 24 mars 1951), Anton Dermota souhaité par Furtwängler n’étant pas envisageable, de choisir Wolfgang Windgassen et George London qu’il trouvait meilleurs, à la place de Hans Hopf (qu’il qualifie de « Naturbursche ») et Otto Edelmann qui devaient de plus répéter et chanter juste après dans les Meistersinger. Pour la Neuvième, leur heure viendra plus tard, en 1954 avec Furtwängler pour Windgassen, et en 1963 avec Karl Böhm pour London.

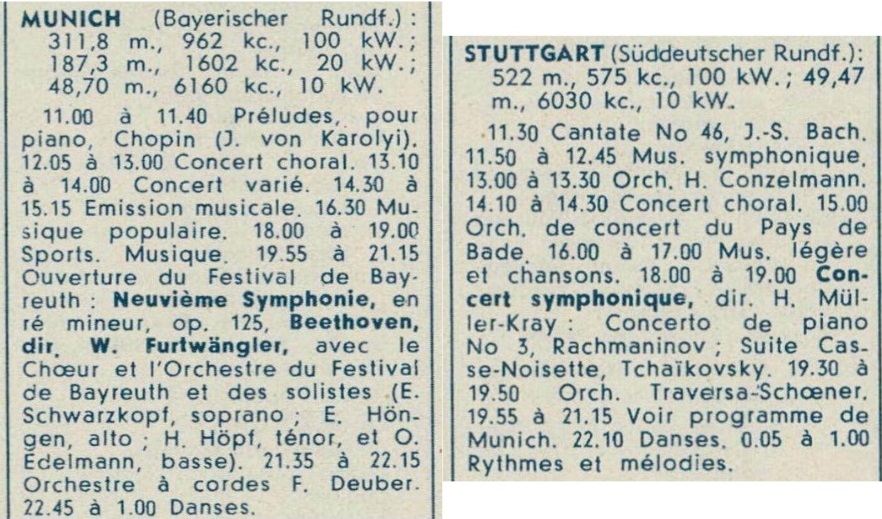

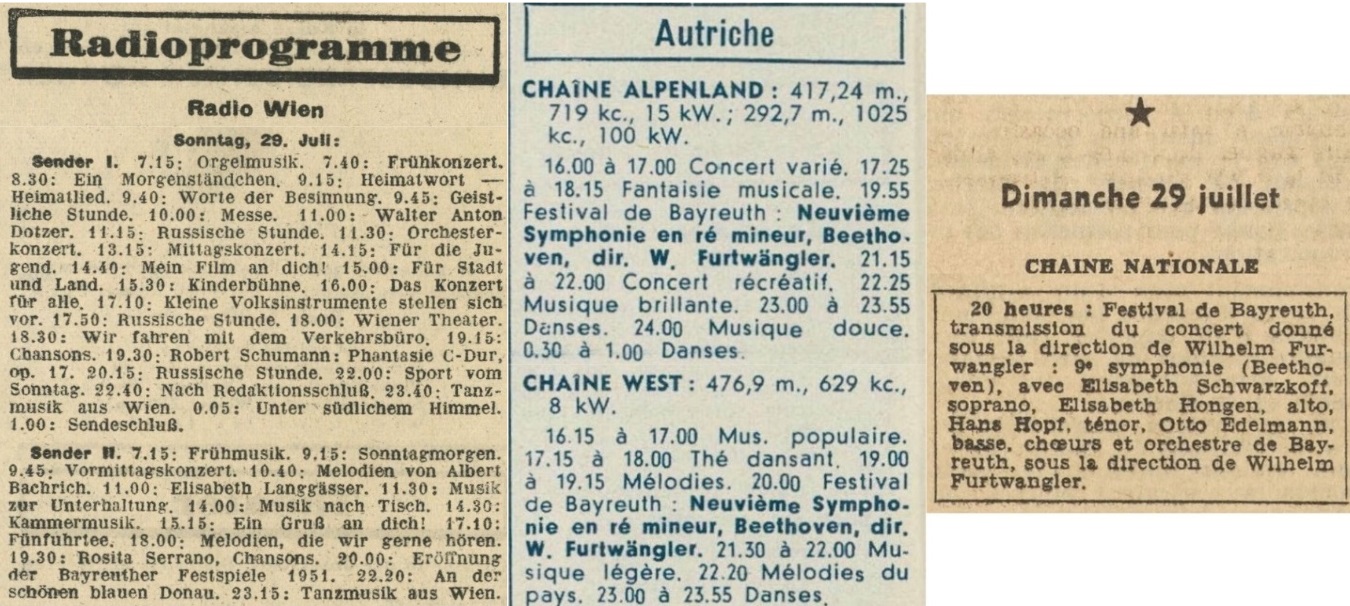

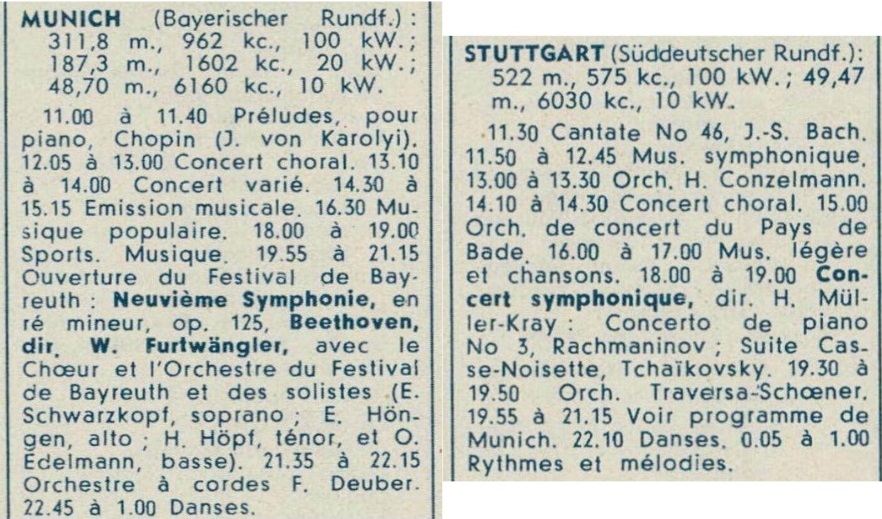

II- La retransmission en direct par la Radiodiffusion Bavaroise:

Le concert a été retransmis en Allemagne par la Bayerischer Rundfunk (Munich) et par la SDR (Stuttgart); en Autriche par la RAVAG (Radio Wien Sender II), le Sendergruppe Alpenland (émetteur de la zone d’occupation britannique) et le Sendergruppe West (émetteur de la zone d’occupation française); en France par la RTF (Chaîne Nationale); et en Suède par la Sveriges Radio (Stockholm, Hörby).

La haute qualité technique de cette transmission est probablement due au fait que la Radio Bavaroise disposait depuis le 18 août 1950 d’un émetteur en Modulation de Fréquence (FM ou UKW). La raison en était qu’après la guerre, les forces d’occupation alliées ont réquisitionné un certain nombre de fréquences en Modulation d’Amplitude (AM), et dès lors, la seule solution trouvée par les radios allemandes pour compenser cette pénurie de fréquences a été la FM, d’où une paradoxale avance technique. En effet, dans les autres pays, ce n’est que vers 1954-1955 que cette technique s’est imposée. On remarquera cependant que dans certains pays, dont la Suisse, une technique permettant une réception de meilleure qualité que la AM était la télédiffusion. Elle permettait aux abonnés de recevoir la modulation par câble sur leur ligne téléphonique.

III- La réception et la fixation par la Radio Suédoise (Sveriges Radio):

Pour voyager de Bayreuth à Stockholm, la modulation a dû (via Munich) cheminer par des câbles sur une très longue distance, en passant à travers un grand nombre de relais pour ré-amplifier le signal qui s’atténue en fonction de la distance.

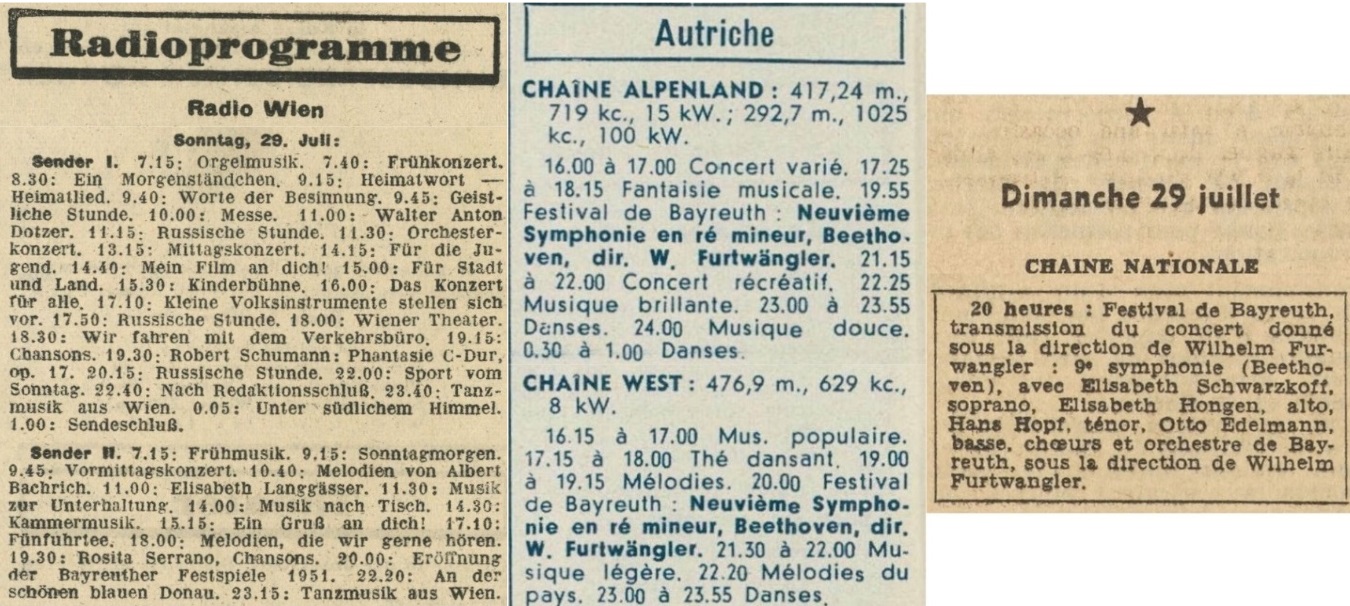

La Radio Suédoise disposait depuis longtemps déjà de Magnétophones AEG K4 (R22), mais pour conserver les enregistrements, elle se servait de disques 33t. à gravure directe, une technique américaine qu’elle utilisait déjà pendant la guerre pour échanger avec les Radios américaines. Le concert que Furtwängler a donné à Stockholm le 25 septembre 1950 avec le WPO a encore été conservé avec cette technique.

A la Radio Suédoise pendant la guerre: de gauche à droite: Henrik Hahr et l’ingénieur du son Hans Sjöström

La Radio Suédoise était également équipée d’enregistreurs à bandes métalliques dénommés Blattnerphone ou Marconi-Stille, et selon les informations connues, les disques à gravure directe des concerts donnés par Furtwängler à Stockholm en 1942-43 avaient été réalisés à partir de telles bandes. Cependant, l’analyse des caractéristiques techniques de ce matériel tant du point de vue de la dynamique que de la bande passante en font douter.

En 1951, la Radio Suédoise a commencé à utiliser les magnétophones modernes pour conserver des enregistrements et c’est à cette évolution que l’on devrait cet étonnant document. Qu’en est-il vraiment?

IV- La publication par BIS en SACD et téléchargement HD:

L’ enregistrement publié par BIS comporte la totalité de l’émission y compris les annonces radio et les applaudissements:

Le site HighResAudio permet de consulter le livret en ligne.

Le livret du SACD BIS porte la mention: Original format: analogue mono tape, digitized by Swedish Radio in 24-bit / 96 kHz, mais il ne donne aucune précision. Notons que BIS a eu l’excellent idée de proposer le document tel quel sans aucun traitement, ni filtrage d’aucune sorte.

Cependant, si on entend bien des bruits électroniques caractéristiques d’une transmission longue distance par câble, on entend également des bruits de surface caractéristiques d’une gravure sur un support mécanique. Par conséquent, la bande numérisée par BIS est très probablement une retranscription à partir du support d’origine (disques ou bande Philips-Miller) qui s’avère de toutes façons incomparablement supérieur à celui qui a servi à fixer le concert du 25 septembre 1950*.

La qualité technique du document proposé par BIS est surprenante, que ce soit du point de vue de la définition, notamment l’ambiance de salle, de la dynamique (très importante) que de la bande passante. Une comparaison montre ce document comme étant presque aussi bon que la meilleure publication de la bande de la Bayerischer Rundfunk, à savoir le superbe (et également dépourvu de traitement) SACD WFHC-030 du Wilhelm Furtwängler Center of Japan, et les bruits de fond provenant tant de la transmission que du support s’avèrent étonnamment faibles. Les défauts analogiques introduits par la transmission longue distance préservent l’intégrité de la musicalité du son (il suffit d’écouter la finesse de définition de l’énoncé pianissimo du thème à 3’05 dans le Finale), alors qu’un traitement numérique de réduction de bruit de fond, même modéré, s’il avait été utilisé, aurait détérioré audiblement la musicalité du son. De la part de BIS, une magistrale leçon de musique et de psycho-acoustique!

* On note cependant dans le Finale une nette dégradation de la qualité du son à partir de l’entrée du ténor.

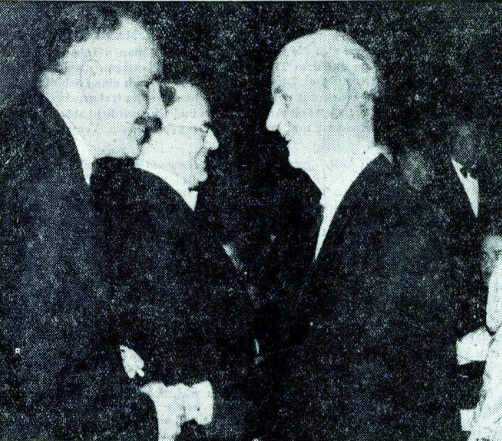

A la fin du concert, Furtwängler sert la main du Dr. Franz Strauss, le fils de Richard Strauss

Beethoven Symphony n°9 Op125 Das Festspielorchester – Das Festspielchor Bayreuth

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth Höngen,Hans Hopf, Otto Edelmann

Dir: Wilhelm Furtwängler

The Swedish record company BIS has recently issued both as a Hybrid SACD (BIS-9060) and as a Hi-Res download (24 bits/96 KHz) the recording made by the Swedish Radio of the Bavarian radio (Bayerischer Rundfunk) live broadcast of this concert, which has unexpetedly survived in its Archives.

It is known that the EMI issue is an edited version which, according to Henning Smidth, is comprised mostly of rehearsals and only partly of the July 29 concert. Said rehearsals are most probably those held on the morning and on the afternoon of the concert, because on July 27, the day Furtwängler arrived at Bayreuth, and on the 28, the first rehearsals took place in another acoustically different hall (see the picture above) and, according to Klaus Lang, with a somewhat different orchestral setup than the classical one for the concert.

For this first postwar Festival, the orchestra was comprised of a total number of 150 musicians, of course not all of them playing here, coming from 40 different orchestras from West Germany (BRD), including Berlin, and East Germany (DDR). For the Ninth Symphony, the choir was comprised of 150 choristers from the German Operas, augmented by 110 choristers coming from Bayreuth. All these musicians were assembled on the stage and on the covered orchestral pit. One easily imagines what tour de force it meant from the point of view of conducting technique to built up in such a short time this performance with such a huge number of performers coming from so many places and who had never played together.

I- The letters between Wilhelm Furtwängler and Wieland Wagner:

Wieland Wagner could only obtain from Furtwängler to conduct in Bayreuth this Ninth Symphony. He also refused to conduct a second performance on August 20.

As to the soloists, Wieland Wagner did not succeed in convincing him (letters of February 5 and March 24, 1951), while Anton Dermota who was Furtwängler’s choice was not vailable, to choose Wolfgang Windgassen and George London he thought would be better, instead of Hans Hopf (whom he called « Naturbursche ») and Otto Edelmann who moreover had to rehearse and sing soon after in Meistersinger. For the Ninth, their day was to come later, in 1954 with Furtwängler for Windgassen, and in 1963 with Karl Böhm for London.

II- The live broadcast by the Bavarian Radio:

The concert was broadcast in Germany by the Bayerischer Rundfunk (Munich) and by the SDR (Stuttgart); in Austria by RAVAG (Radio Wien Sender II), Sendergruppe Alpenland (broadcasting stations of the British occupation zone) and Sendergruppe West (broadcasting stations of the French occupation zone); in France by RTF (Chaîne Nationale); and in Sweden by Sveriges Radio (Stockholm, Hörby).

The high technical quality of this transmission is probably due to the fact that the Bavarian Radio had since August 18, 1950 a Frequency Modulation (FM or UKW) broadcasting station. The reason was that, after the war, the Allied occupation forces had requisitioned a certain number of Amplitude Modulation (AM) frequencies, and thus, the only solution found by the German Radios tto overcome the shortage of frequencies was FM, hence a paradoxical technical advance. Indeed, in other countries, it was not before 1954-1955 that this technique was implemented. In other countries, like Switzerland, there already existed a technique allowing a better quality than AM, namely telediffusion. It allowed to subscribers to receive the broadcast signal by cable on their telephone line.

III- The reception and recording by the Swedish Radio (Sveriges Radio):

To travel from Bayreuth to Stockholm, the broadcast signal had to travel (via Munich) through cables over a very long distance, and to go through a great number of relay stations to re-amplify the signal to compensate for the attenuation of the signal along the cable.

The Swedish Radio had since long AEG Magnetophones K4 (R22), but to keep the recordings, it rather used 33rpm direct cuttting discs, a US technique it already used during the war to exchange with the US Radios. The concert Furtwängler gave in Stockholm on September, 25 1950 with the WPO was still archived using this technique.

Swedish Radio during the war. From left to right: Henrik Hahr and recording engineer Hans Sjöström

The Swedish Radio also had steel tape recorders called Blattnerphone or Marconi-Stille, and the known information was that the direct cutting discs of the Furtwängler Stockholm concerts given in 1942-43 had been transferred from such tapes. However, the analysis of the technical data of this equipment both from the point of view of dynamics and bandpass makes this idea moot.

In 1951, the Swedish Radio started using modern tape recorders to keep recordings and it is to this evolution that this astonishing document is supposed to be due. Is it really true?

IV- The publication by BIS as SACD or Hi-Res download:

This recording as published by BIS is comprised of the complete broadcast including the announcements and applause:

The site HighResAudio allows to read the booklet online:

The BIS booklet bears the mention: Original format: analogue mono tape, digitized by Swedish Radio in 24-bit / 96 kHz, without any other information. Note however that BIS had the excellent idea of proposing the document « as is », namely without any treatment or filtering whatsoever.

However, if electronic noise characteristic of a long distance transmission is heard, surface noise characteristic of the cutting of a mechanical surface is also present. As a consequence the tapes digitized by BIS are most probably a transfer from an original support (discs or Philips-Miller tape) which anyway is vastly superior to the one that was used soon before for the said concert of September 25, 1950*.

The technical quality of the document proposed by BIS is surprising, from the point of view of definition, especially hall ambiance, dynamics (quite huge) as well as bandpass. A comparison shows this document as being almost as good as the best issue of the tape from the Bayerischer Rundfunk, namely the superb (and also unprocessed) SACD WFHC-030 (Wilhelm Furtwängler Center of Japan), and the background noise from transmission and from the support have an astonishing low level. The analog defects from the long distance transmission preserve the integrity of the musicality of the sound (hear the subtelty of the pianissimo playing of the theme at 3’05 into the Finale), whereas an even moderate digital noise reduction treatment, had it been applied, would have damaged the musicality of the sound. From BIS, a masterful lesson of music as well as of psycho-acoustics!

* There is however in the Finale an important loss of sound quality after the tenor entry.

At the end of the concert, Furtwängler shakes hands with Dr. Franz Strauss, son of Richard Strauss